One and a half years since the grand opening of Crip Arté Spazio: The DAM in Venice, and 8 years since his passing; Keith Armstrong's extensive photographic and unique archive continues to make waves. Why has he caught so much attention? In many ways the reasons might be quite obvious, however as the rights and support for disabled people in the UK remains ever turbulent, there is more to why Keith's work has been considered as not just a highlight of the show, but an archive that deserves an audience and attention.

When I visited Crip Arté Spazio at Crea in Venice in the summer of 2024, a lot was happening. The next US election was on the horizon, the UK was making plans to slash benefits in the new year and Italy was throwing around ideas to crackdown on protest laws. During those few days I was visiting the show, Georgia Meloni (the current president of Italy) released the news of an upcoming bill containing 24 laws, with heavy focus on increasing police power during protests. It would allow authorities to enforce fines and jail time on protestors, particularly those targeting public roads and building projects such as the TAV - sounds familiar, no? I'm looking at you HS2 / PIP cuts / Extinction Rebellion...

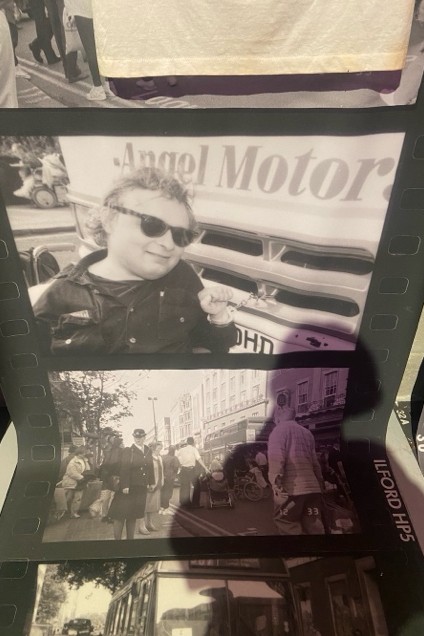

In the exhibition itself, I entered the large gallery space through wide open doors before slipping through tall wooden letters that spell out 'SPAZIO' - the A is missing to let you through - we are immediately faced with Keith's work, a peek into his extensive archive. Trailing down the high ceilings and spilling out onto the floor, large photographic prints of Keith's film rolls depict scenes from protests in the battle for disability rights in the UK, particularly during the early 90s when the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) came as a result of some of these actions. We are faced with image after image of protestors amidst the public actions, red double decker buses, cardboard placards, police officers and film crews.

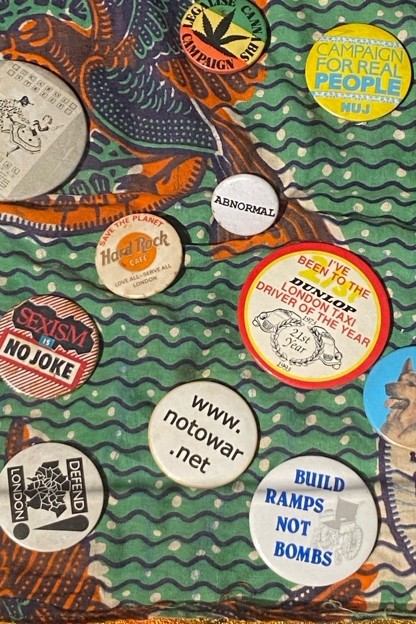

Four off-white t-shirts with muddy stains on the right shoulders are suspended across some of these images in a line. Standing at the end of these film rolls, inviting you in to look closer, is a square glass vitrine supported by a thin metal structure that reads 'RIP KEITH ARMSTRONG' as you circle around it. Swarming a vivid green section of batik-style fabric inside the vitrine are endless campaign badges from a wide range of initiatives (I counted around 227 badges for sure), with a small toy red double decker bus parked diagonally in the middle. This object is Keith's funeral shroud; a memory of his expanded campaign work, and a reminder to those continuing the fight, that so many initiatives are campaigning for similar goals - rights, support and community.

Standing in the exhibition, already with this news from Meloni, there was an even bigger richness to Keith’s archive and collection, highlighting that our presence and voices can make change even up against multiple barriers - they found a way. Keith's archive shows the fight for the rights of marginalised people. It’s a snapshot not only into the lives of disabled people of that time, but also into Keith's extremely interconnected life. But it’s important to note, that the archive on display as part of the exhibition, is only the tip of the iceberg. NDMAC and the Bishopsgate Institute hold extensive archives of not only his protest photography, but also music, poetry, typewriter artworks and prints. Academic papers are accessible through Academia.edu.

Looking up in the gallery away from his work, booming overhead are two screens playing interviews by the show’s curator, David Hevey with artists Tanya Raabe-Webber, Jason Wilsher-Mills and Tony Heaton OBE - almost sitting in dialogue with the history that oozes out of Keith's work below. These interviews shed light on these artist's own lived experience making art in the context of Disability Rights and how these experiences have brought them to make their work today. Hearing the voices of these important figures in the movement, who continue to campaign today, carries an even heavier meaning now (in 2025) - with the fight having re-erupted again with increased public protest against current welfare cuts in the UK. Keith's photos could have been taken today and takes space as the stark reminder that the hardcore work of activists doesn't stop - and is a constant battle.

Image of Tanya Raabe-Webber is a screenshot taken for her interview film by David Hevey.

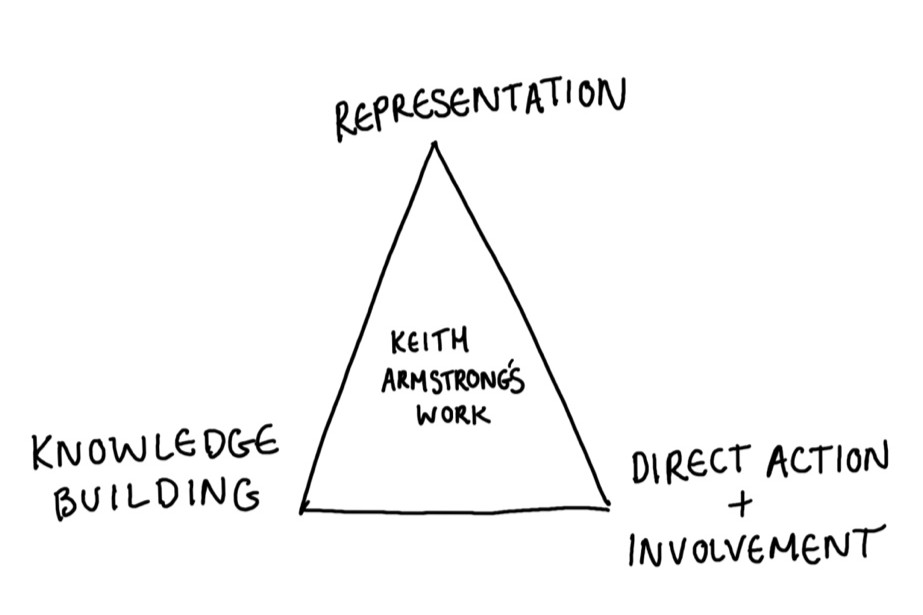

So, who was Keith Armstrong? Arriving in London in 1972, (aged 22), Keith was already breaking down barriers and bringing his own lived experience into his political work. I couldn't ignore the fact that Keith was somehow 'everywhere' and managed to bring many marginalised voices to the forefront in many aspects of society. And it wasn't just disabled people. The funeral shroud can really speak to this in a tangible way, but for me it felt like he operated in this triangular approach which really drove his work forward and covered so many struggles, not just the fight specifically for disability rights.

This is what I mean when I say triangular approach and I'll share some examples below:

- Representation - He was the first member with a disability at London Transport Passenger Committee in 1983. Keith was a trailblazer, paving the way for more disabled voices in these spaces.

- Direct action and involvement - Working in his local area, he was actively involved in the Tenants Right to Unite in Somers Town (TRUST). Keith was present in protests, supporting initiatives that empower people facing.

- Knowledge building - He was an active member of the Camden Community Law Centre and even stood for local election Somers Town Ward, Camden Council, under the banner ‘Accessible Labour’. Keith was understanding the laws and systems that he was currently living in and applying that knowledge to help make policy change. His academic papers also speak to this.

Something perhaps also important to flag in all of this, is Keith's education before his transition to London. He attended the National Star Centre for Disabled Youth near Cheltenham, something that I feel is interesting to include. I appreciate in an ideal world perhaps the 'perfect school' reflects a barrier-less environment with total inclusiveness, but I wonder whether maybe this particular school gave him the support he needed to focus on campaigning and supporting others - removing the discrimination he could have experienced at school at a young age. It perhaps gave him the space to look outwards, away from impairments to wider systemic barriers people face, at a time when the medical model arguably took hold of the narrative around disability. I wonder if his particular experience of education helped enable him to do all the work he did down the line.

Image credit, Emily Roderick. T-shirts hung in the exhibition, Crip Arté Spazio: The DAM in Venice.

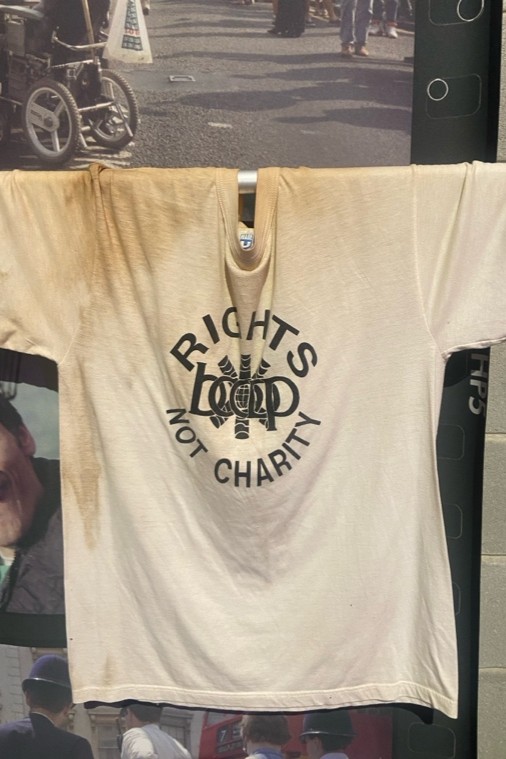

Like many disabled activists, a handful of messages are central to Keith's work, 'disabled rights now', 'rights not charity' and 'nothing about us with us'. I get the feeling he was well connected, just always there either out campaigning in the streets, or inviting people into his home to build support networks. He perhaps was a familiar face constantly working for change - but what really strikes me is this intersectional or, as Keith might have called it, socialist approach, particularly acknowledging the quite baffling range of campaign badges the shroud holds to this day. This collection documents that journey, as an individual and the personal connections he made, but also highlights the bridges to multiple communities that he built and supported.

The badges point to various campaigns including:

Improving London’s public transport services, the 1984–85 UK miners' strike, stopping welfare cute in Camden, anti-racism in Ealing, stopping nuclear power, a free Palestine, standing against sexism, keeping train guards on trains for safety, encouraging the use of BSL, fighting censorship (in light of the McLibel case) and stopping the Iraq war – to name just a few.

Image credit, Emily Roderick. Close up images of sections of Keith Armstrong’s Funeral Shroud in Crip Arté Spazio: The DAM in Venice.

Perhaps though my favourite badge is the one that reads ‘Wearing badges is not enough’. A slight joke to his own collection but also a strong message. I believe he did much more beyond badge wearing, whilst keeping the humour present.

Image credit, Emily Roderick. Close up image of the badge ‘Wearing Badges is NOT ENOUGH’ on Keith Armstrong’s Funeral Shroud in Crip Arté Spazio: The DAM in Venice.

But why did he make the work he made? There is a journey from the badge on the shroud, to the photo in the protest, to the direct action/change made. Subversiveness comes to mind, and also the desire to document a moment of real change in UK policy - even if he didn't know it yet.

Keith's photography was not only documenting a moment of change in disability rights, but he was documenting the real struggle disabled people went through to fight for these changes. There is something really powerful in seeing disabled people of that time protesting in public space, and seeing up close the situations they had to put themselves in. Whether it’s a line of 20 wheelchair users waiting for the same bus (a bus without a step-free entrance at that time), placards sharing messages demanding change - held by disabled people who are affected most, or people quite literally taking up space in a road in defiance. Their physical presence was part of that demand for change, something that is even more tricky to navigate as a disabled person in a society not built for them.

A common thread through these images are the standoffs between disabled people and police officers - it's lived experience against the state - open arms against disabling barriers. Back in the 80s and 90s the police in these images were stuck not knowing what to do with disabled activists as police vans and stations were widely inaccessible. The choice to try and remove the right to peaceful protest in recent times, also removes the opportunity to even access public spaces together in this way. Restrictions like these are keeping barriers in place, and often expanding them. It makes me reflect on policing and the approach to protestors that the police force has today. Has it really changed? a time where journalism is also under threat, this raw photography brings awareness to the full stories that need to be shared. Having direct footage like Keith’s archive, of the people involved, BY the people involved is paramount.

When we aren't focussed on the presence of police in some of these photos, Keith also captures the very physical nature of protest. The more joyful moments of togetherness that show the compassion and empowerment that collective action can do. The photographs show the struggle, but also the joy of community. Increasingly people need more money and time and face fewer barriers to being together in public space in order to protest.

He’s a creative wearing many hats. Like many people facing barriers in the arts/culture/activist circles, juggling multiple responsibilities to make ends meet is very common. He’s a bridge builder - highlighting the integral overlaps between art and politics with his work, arguably something that the art world continues to be very wary of - particularly when so many artists are relying on public funds that require some ambiguity around active political stances. Funds are directed to storytelling and analysis thereof, rather than art that directly leads and fuels political action. I get that. We also need art that isn't inherently political, that speaks to other needs. But it does make me think about the power that Keith’s archive captures and the story it richly narrates.

More specifically in Crip Arté Spazio, Keith’s archive is contextualising the exhibition and building the historical narrative (also present in the comic strip style narration that lines the exhibition walls). A big reason as to why I'm so fascinated by his work is because of the lived experience it carries. He's someone that's been able to capture the action and concretely document it whilst also take part in the protest and campaign. He's grounded the contemporary work of artists today in a well-documented and successful fight for disability rights, contextualising the shift in aesthetic and narrative connected to disability rights now - particularly with the inclusion of Jameisha Prescod, Abi Palmer, Terence Birch and Ker Wallwork in the show, who's work speaks to a new generation of disabled artists and activists - 30 years on. But also, through documenting the struggle rather than the win - intentional or not, his photography is keeping that narrative open rather than a closed chapter, which feels right in the current state of things in the UK. Is the archive highlighting that the struggle continues? Is it suggesting that art can always be a way to connect people in different ways to these historical moments. The exhibition gives power to marginalised voices with lived experience, back in the 90s I wonder how often this was the case. Writer and curator, Kenny Fries flags an important point in his review about the theme of the Venice Biennale - "Foreigners Everywhere includes few self-identified disabled artists". The fact that Keith was disabled himself also brings in the reminder that we need disabled representation and authorship - and we need more of it! So the question moves to how can more disabled people have access to the room/votes/power/change making? How can this happen? What barriers need to be removed?

We are still lacking support for the largest minority group in the world - disabled people. So, opening up a significant archive connected to the history of the disability arts movement and disability rights - it’s not just about Keith's work being in the show actually, that’s not the most exciting bit in my opinion – for me it’s the knowledge sharing and exposing a deeper the history of the DAM. Maybe people can connect more to Keith's collection - is it perhaps a more accessible medium? More direct? Whilst also having layers, stories and experiences that unfold in each item.

Experiencing Keith's archive across the backdrop of the multitude of current fights for rights across the UK - perhaps his work acts as a reminder that whilst telling a story of the struggle for disability rights, it also inspires for future campaigns. It makes me think that his work is also acting as an invitation, a blueprint to work towards in the ongoing battle for disability rights, and how art can be a powerful tool within this conversation, allowing more people learn about the struggles faced by disabled people. His archive is saying 'look we're here, this is what we've experienced, and this is what we need'. If you give voice only to the people in power, you erase the struggle of the people actually facing those barriers.

Presenting an archive like this also comes at an interesting time when we are witnessing a lot of news content in real time - live streams, frequent articles and a constant flow of reporting. What does stories of protest look and sound like today? The protest photographer now sits against the police body cam. It’s a different dynamic now. With increased surveillance and the possibility of blanket bans on face coverings at protest it’s a different landscape and a time where increased education around people’s rights are needed. Are we witnessing a change in the control of disabled people? How might Keith's work look now 30 years later?

There is a great sense of community, and the joy in campaigning together in public spaces – that Keith’s work tries to tap into. Not just the desire for change, but also the desire for togetherness and joy, and how the ongoing fight for disability rights is a fight for everyone.

Closing this blog post, I invite you to look deeper and consider some of the following actions:

- Visit the archive online at NDMAC, or in person at Bucks NDMAC Repository and at Bishopsgate Institute

- Find out more about your rights and how to advocate for them

- Explore your local community and find ways to connect with each other

- Don’t forget to document! Take inspiration from Keith and capture what’s happening around you.

Image credit, Emily Roderick. Taken inside the exhibition Crip Arté Spazio: The DAM in Venice. Emily’s silhouette partially covers a long printed reel of Keith’s images – one of which is himself chained to the front grill of a bus. His fist is clenched, he wears black sunglasses and has a slight smile.

Images included in this piece are from NDMAC archive unless otherwise stated.

Emily Roderick (she/her) is a freelance artist, producer and access support worker. She currently supports Shape Arts as Assistant Producer in their NPO programme and NDMAC heritage projects including Crip Arte Spazio: The DAM in Venice. Emily was a co-founder of the artist group The Dazzle Club exploring surveillance in public space. She completed a DYCP from Arts Council England exploring English change ringing and performance in early 2024.