In 2024, Shape Arts brought a revolutionary slice of British art history to one of the world’s most prestigious cultural stages: the Venice Biennale. Crip Arte Spazio: The DAM in Venice marked the first ever major international exhibition dedicated to the UK’s Disability Arts Movement (DAM). Curated by Shape Arts CEO David Hevey and designed by Nina Shen, the show was a vibrant, defiant tribute to a movement that has challenged politics, redefined art, and reshaped disability rights over the last five decades.

Through this lens, we share the story behind the story: how a radical movement was reframed, reinterpreted, and amplified for one of the world’s most prestigious art platforms stages, and how that process in itself was an act of political disruption.

Starting with a Question: Why Not the DAM?

The idea for Crip Arte Spazio was born from a provocation. In 2017, Shape Arts CEO and DAM artist David Hevey visited the Diaspora Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. That exhibition rejected the traditional national pavilion structure of the Biennale and gave space to artists connected by diasporic experience. The impact was bold, unapologetic and fresh.

For Hevey, it sparked a thought: if the Biennale could open itself to that kind of redefinition, why couldn’t the Disability Arts Movement occupy the same space?

The Disability Arts Movement has transformed British culture since the 1970s, using art as a vehicle for disabled people’s rights, voice and power, but it had never been given international stage time. Hevey believed it should be and not just as representation, but as disruption. “I wanted to explore the people, stories, radical ideas and radical art behind the DAM,” Hevey explains, “conveying the exuberance and resistance of one of British history’s great political art campaigns.”

The vision was clear: create the first international group show of DAM artists; challenge the conventions of disability representation in the arts; and take it to Venice.

Exhibition as Invention: Designing from Scratch

The exhibition was hosted at CREA Cantieri del Contemporaneo, a repurposed shipyard on the island of Giudecca. From the outset, exhibition designer Nina Shen and Hevey rejected the aesthetic of the ‘white cube’ gallery. Instead, they wanted to create a visual and spatial language that felt rooted in the street-level activism from which the DAM had grown.

Very little in the final space pre-existed Crip Arte Spazio, almost everything was custom-designed for the show. That included enormous banners, industrial-style letter signage, oversized comic panels and even sliding-door entryways that echoed protest signage. “With the exception of the artworks and the Keith Armstrong heritage materials, none of this existed before,” Shen explains. “It was all a complete invention and a process of active re-interpretation.”

The design research was exhaustive. Shen and Hevey visited over 150 exhibitions across London, Berlin, São Paulo, New York, Kassel and Cologne. What stood out wasn’t inside museums, but outside them: street posters, activist murals, pop-up interventions in public space. These vibrant, makeshift, multilingual design languages felt more urgent and honest than the polished minimalism inside galleries.

The result was a show that visually echoed the DAM’s politics. Loud, graphic, celebratory and critical. The design elevated the artworks and mythologised the movement. “We imagined the exhibition as if the DAM had won every battle,” Hevey says. “As if it was now eternally triumphant, which is how history should have been.”

A Movement in Three Generations

The artists featured in Crip Arte Spazio spanned three generations of the Disability Arts Movement, carefully curated to reflect both its origins and its contemporary evolution.

Founding figures like Tony Heaton OBE, Tanya Raabe Webber and Jason Wilsher-Mills represented the radical foundations of the DAM, artists who fused politics and creativity in defiance of both art-world norms and social stigma. Their work confronts audiences with power, humour, and a refusal to conform to ideas of pity or limitation.

NDMAC supported the Crip Arte Spazio, and became central to the project

Photographer Keith Armstrong’s work provided the historical backbone and wraparound of the show. Sourced from the National Disability Movement Archive and Collection (NDMAC), which is collecting the heritage story of the UK Disability Rights Movement, his protest photography captured the grassroots disabled activism of the 1980s and 90s—from transport blockades to street marches. Armstrong’s ‘Funeral Shroud’ of protest badges and t-shirts, also on display, was a powerful visual eulogy to the personal and political stakes of the movement, a fight to remove barriers. More than most, Armstrong’s imagery exemplifies the NDMAC tagline: crip fights for civil rights!!

New wave artists Ker Wallwork, Abi Palmer and Jameisha Prescod were selected by curatorial advisors to represent the future of the movement. Working across film, digital media, installation and performance, these artists reflect the DAM’s shift into digital spaces and its continued commitment to radical, intersectional storytelling.

By bringing these artists together, the show positioned the DAM as an evolving political and aesthetic ecosystem, not just a historical moment, but a living, breathing, forward-moving force.

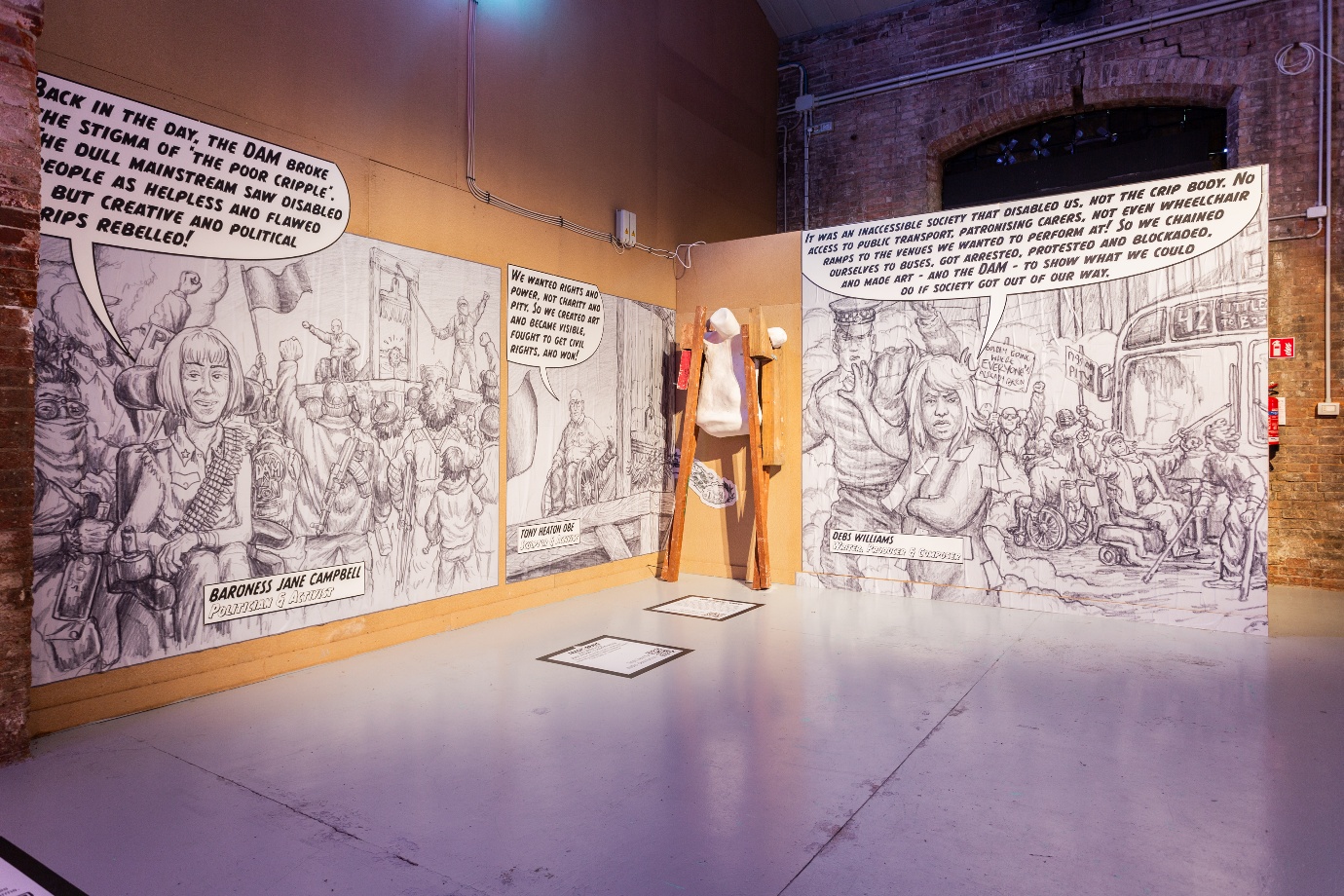

Framing Conflict Through Comics: Visual Storytelling as Political Weapon

One of the exhibition’s curatorial elements was a set of large illustrated interpretation panels created by artist Simon Roy and produced by Liam Hevey. These graphic panels served a dual purpose: to contextualise the movement for new audiences and to mythologise its political fight in bold, comic-book style.

The imagery combined real historical events, such as Vik Finkelstein’s development of the Social Model of Disability, or protestors handcuffing themselves to buses with exaggerated, satirical scenes: DAM artists storming Venice; Barbara Lisicki leading an army; an art-world official guillotined by a giant paintbrush.

These panels weren’t just educational, they were theatrical. They asked the viewer to feel the weight of the DAM’s history, and to see disabled people not as victims, but as heroes in a decades-long campaign for justice.

In Hevey’s words, “We wanted to engage audiences with an inspiring, mythologised version of the struggle, because the truth is, many of the values the DAM fought for, access, equality, freedom, are now being rolled back. So, the DAM doesn’t just belong to the past; it shows us how those ideals can, through political conflict, be won again.”

Naming, Framing, Reclaiming

The title Crip Arte Spazio, literally, “Crip Art Space”, was chosen with purpose. The term ‘crip’ is a reclaimed slur, now used by many in the disability community as a term of empowerment, defiance and shared identity. Using the term unapologetically in the title of an international exhibition was itself a radical move.

‘Crip’ signals that this was not a neutral or ‘inclusive’ show. It was a political declaration. The exhibition didn’t aim to ‘integrate’ disabled artists into a normative art world; it aimed to challenge the values of that world altogether.

That tension was deliberate, and essential. Crip Arte Spazio wasn’t just about disability representation; it was about shifting where power lies. As Hevey explains, “What I wanted to convey was the overriding sense from all the artists of their pursuit of justice and power. Power for disabled people, power in their lives, power in their art, and, one hopes, power to change the art world too.”

Access as Aesthetic, Not Afterthought

The exhibition featured audio descriptions, BSL content, large-scale text, tactile design elements and digital access points. These weren’t add-ons; they were part of the show’s aesthetic and conceptual framework.

The result was an experience where access tools didn’t feel like accommodations, they felt like extensions of the art itself. By making access integral, the curatorial team positioned disabled visitors as primary, not secondary audiences.

That ethos extended to the exhibition’s digital life. With over 2 million online engagements, Crip Arte Spazio became a hybrid exhibition available to those who couldn’t travel to Venice, or who might not access traditional art spaces. In doing so, it echoed the DAM’s early tactics of circulating zines, newsletters and DIY media: making sure disabled audiences were always included in the conversation.

Challenging the Biennale from Within

Perhaps the exhibition’s most radical gesture was its positioning. While not part of the official Biennale programme, Crip Arte Spazio ran in parallel occupying the same city, during the same timeframe, speaking to the same global audience.

It deliberately refused national representation. It wasn’t “the UK pavilion” or a state-sanctioned display. It was an insurgent space like the DAM itself, a grassroots campaign gone international.

In that spirit, the exhibition asked a powerful question: What would an art world look like if it were designed not around prestige and exclusivity, but around protest, plurality, and power from the margins?

Legacy and the Long Game

Crip Arte Spazio took years to develop. It was made possible through the support of Arts Council England, British Council, National Lottery Heritage Fund, Creative Scotland and CREA Venice, but also through the long, patient work of building trust with artists, activists, archivists and advisors.

Its legacy is more than numbers (though the numbers are impressive: 24,000 in-person visitors, 2 million+ online). Its legacy is the provocation it leaves behind.

It asked: what role does art have in political struggle?

It showed: disabled artists have always been there, leading that fight.

It proved: disability arts doesn’t just deserve space, it can redefine what art space is.

At its core, Crip Arte Spazio challenged the international art world to think differently, not only about disability, but about representation, access, and value. It asked: what does it mean for disabled artists to be centre stage, not on the margins? What happens when their struggles and creativity aren’t separated, but celebrated as intertwined?

Hevey puts it simply: “What I wanted to convey was the over-riding sense coming through all eight artists of their pursuit of justice and power—power for disabled people, power in their lives, power in their art. And, one hopes, power to change the art world too.”

About the author

Rebecca Wymant is a curator and visual arts professional based in the East Midlands, working across the region and in London. She has held roles in leading museums and galleries, contributing to significant exhibitions both in the UK and internationally. In addition to her institutional experience, Rebecca undertakes freelance projects in curating, writing, and consultancy, collaborating with a range of arts organisations. She is particularly passionate about disability arts and the power of visual storytelling.